Articles

TEXAS STUDIO: SUSAN BUDGE INVITES YOU INTO A WORLD OF MYTH AND MYSTERY

Donna Tennant, Arts and Culture Texas (ACTX), August 8, 2023

Over the span of six months in 2022, Houston sculptor Susan Budge lost her mother, got married, saw her son graduate from high school, built a kiln in a new studio, and was diagnosed with breast cancer. A few months later, she completed a major installation for Brackenridge Park in San Antonio.

“I also had a solo show scheduled for October at Heidi Vaughan Gallery,” Budge said. “When I couldn’t fill the gallery myself, I asked a few of my artist friends to be in the exhibition.”

The exhibition, Transcending, was about transcending cancer and other personal challenges through art. “Because of my surgery, I could only work on small pieces for four months, like the stars for The Silos and my jewelry.” Budge returns to Heidi Vaughan Gallery for a new solo show in October.

Budge is a ceramic sculptor who has worked with clay her entire career. “I started digging clay from my grandparent’s pond in Palestine when I was about five,” she said. “My grandfather was a landscape painter, so I was always encouraged to make art.”

When Budge was in college at Texas Tech, she had several different majors before finally realizing her calling. “I would take a ceramics class each semester as a reward for my other classes,” she said. “My senior year, I finally switched my major to art.”

Her sculptures are often figurative and life-size, suggesting guardians, sentinels, and goddesses. Budge works on a large scale so that her pieces can achieve a strong physical presence.

“I prefer to work spontaneously in the studio in order to allow my subconscious thoughts to surface,” she said. “Afterward, I try to figure out why my sculptures look the way they do.”

Yet another influence is the natural world, and her work includes birds, spiders, oak leaves, aspen trees, nests, and eggs. Budge’s home and her ceramics studio are located on several acres of bucolic land near Brookshire, Texas, where her view includes trees and cattle. The studio is the culmination of a dream after a peripatetic career that included two decades in San Antonio as a tenured professor and head of ceramics at San Antonio College.

Though Budge was born in Midland, Texas, her father’s profession as a geologist in the oil and gas industry took the family all over West Texas and New Mexico, with stops in Corpus Christi, Carlsbad, and Albuquerque. After college, Budge moved to Dallas and then Houston, where she worked in various jobs to support her art career. After receiving two Texas Commission on the Arts grants to work with students in Victoria and Levelland, she discovered a love of teaching.

While working at San Antonio College and pursuing her MFA at the University of Texas San Antonio, Budge applied for several public-sculpture projects. Three pieces are now on permanent display in San Antonio’s Brackenridge Park. Anaqua is a bright red bird holding an anaqua seed in its beak. The anaqua tree was important for the Native Americans who lived in the area, as the berries are edible and the dense wood excellent for making tools. The second piece titled Quercus is a large oak leaf, and the third, Acequia, references rippling water. All three pieces are installed on tall triangular towers constructed with large stones from the park.

In 2008, Budge did a series of installations for Myth, Magic, and Mystery at the San Antonio Botanical Gardens. They included her first fountain piece, Sirens. Three undulating figurative pieces installed in the pond there reference the temptresses from Greek mythology who would lure sailors to their death. Sirens occupy a recurring place in art as an avatar of female sexual power, and many of the artist’s sculptures suggest sensual feminine figures.

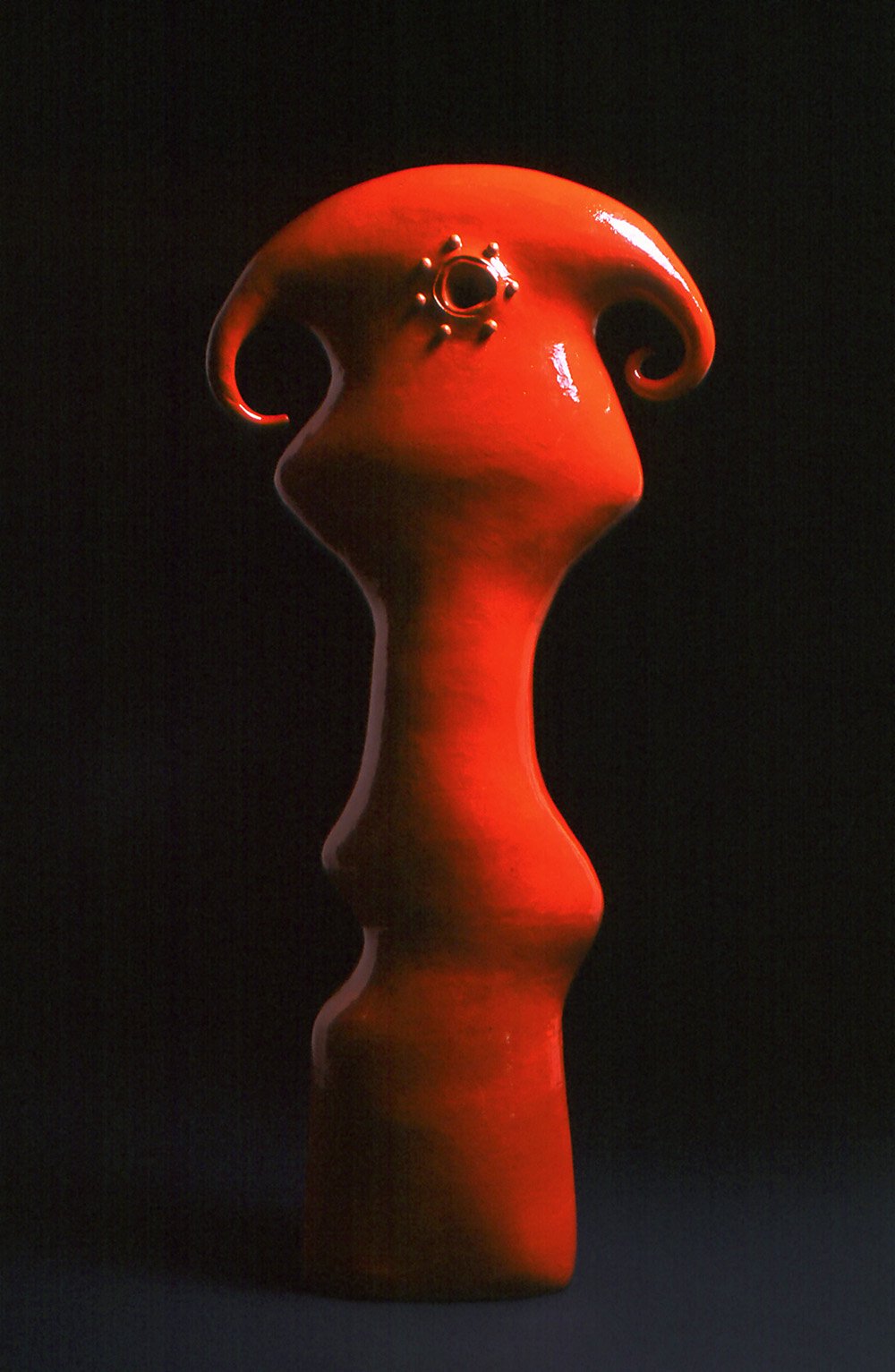

Budge’s work often references Paleolithic goddess figure forms symbolically linked to motherhood and fertility. After creating the red sculpture Eros, one of her collectors who is an endocrinologist said it resembled the female reproductive system. Around that time, she was also creating nests filled with eggs. “I was starting menopause,” she said, “and then I unexpectedly got pregnant and had William in 2003. That changed everything.”

As a single mother, she would bring him to the studio while she worked and noticed that he was always watching her. Soon realistic eyeballs began appearing in her sculptures.

“Having William altered my attention to proportion and scale,” Budge said. “I didn’t think I could work small, but then I started making smaller pieces. I began doing all this meticulous work, and I couldn’t figure out what it was about until one day, I was cutting up a hot dog for him. I realized that cutting all his food into tiny pieces was becoming part of my process.” This is reflected in beaded sculptures like Eye Spy Cherries.”

For Budge’s 2021 installation in Altamira, The Primal Urge to Create at The Silos in Houston, she suspended a large eye looking down at the viewers. “When you go into a silo, you always look up,” she said, “so I hung a large eye and added all these little eye stars looking down on people.”

To continue the concept of being watched, Budge installed a surveillance camera inside the big eye and a video screen outside so people could observe the interior. She had children coat their hands with Elmer’s Glue and blue glitter and make handprints on the walls to reference the prehistoric cave paintings. She placed a large sculpture in the center of the circular space and scattered small eye spy sculptures around the perimeter. For the sound element, her husband, musician Rick Paulson, mixed Stardust by Willie Nelson with night sounds from their farm. “Stardust was my grandmother’s favorite CD, so it was just perfect,” she said.

Budge’s work has always reflected her emotional state of mind. Sculptures of cactuses reflected a desire for solitude. A red heart impaled with steel shards followed a period of heartbreak. “When my life gets stressful, I return to the narrative,” she said. “When I am in a period of calm, I do more meditative work.”

Most of Budge’s pieces are constructed from slabs of clay with little use of the potter’s wheel. When she works with wet clay, she is tapping into the collective unconscious, connecting instinctively with the ancient past. Humans mixing clay and water to create utilitarian articles dates back to the later Paleolithic period. This activity transcends creating objects of beauty—it is both a sacred and profane endeavor that transforms the clay. Many of Budge’s sculptures reference archetypal figures that allude to the mystery of the human subconscious.

“Touching clay for the first time was an epiphany,” Budge said. “I love balancing its fragility and strength. The physical, sensual, and magical qualities of this material have challenged me for the past 40 years.”

SUSAN BUDGE: REFERENCING

Peter Drake, Ceramics: Art and Perception, 2003 - Issue #53

Referencing. This is the by word of contemporary art practice, the lingua franca and justification for the exchange of ideas between artist, critical theorist and audience. A “Where’s Waldo” for the informed art viewer. Referencing is the art world equivalent of the Shriner’s secret handshake. If you can’t spot the reference then you aren’t a member of the club.

But what happens if an artist’s commitment to their work is so complete, their investment to the evolution of their craft so intuitive that their work embraces the entire history of that craft without the sly nod or the knowing elbow in the ribs? Is this referencing or is it simply what happens when an artist works hard, knows what they are doing and adds in a measure of the ineffable?

Susan Budge makes art that can somehow make a connection to a range of work that includes Paleolithic talismans, early modernism via Brancusi, Miro and Tanguy, thrift store chatchkas and the backgrounds of Hannah Barbera cartoons. These associations aren’t entirely new and yet when they usually show up in an artist’s work they more often than not come with a hefty dose of irony. However, when a really talented artist hunkers down in the studio and roams around the culture and their own psyche looking for meaning, associations magically accrue. You see the connections between south pacific totems and Yves Tanguy. You understand why they wanted Roadrunner’s cacti to look like Brancusi’s Bird.

If the word ecstasy comes from the Greek ex-stasis, to be displaced, then somehow displacement has come to be associated with a kind of exquisite disorientation. This is what I get out of Susan Budge’s work. People have been squeezing together lumps of clay for as long as people have had the free time to do anything. This may be the oldest form of art practice known to man. If you engage in this activity then you are stepping into a slipstream of unbroken human history.

When you look at Budge’s work you can see every moment and every motive of creative human endeavor. You can find sympathetic magic, idolatry, shamanism, fetishization and comedy. You can see the ways that human beings have sought out the connections between high and low art. The exquisite disorientation that you feel is the result of a kind of slingshot free association that happens when the Venus of Willindorf starts to look like Jabba the Hut. One doesn’t necessarily neutralize the other. They don’t call each other into question; they simply call to each other. This visual point and counterpoint is ultimately about faith. The belief that all of this stuff that we’ve been making for so many years actually adds up to something.

One of the popular strategies of the post modern period was the idea that by filtering high modernism through the lens of popular culture you could de-mystify the inflated heroics of a seminal moment in history. In the hands of artists like Peter Halley and Phillip Taafe, this leads to an irreverent deconstruction of grandiose modernist assumptions. In the hands of Susan Budge this same lens seems to be pointing in the opposite direction. Rather than pointing down to pick through the minutia of modernist meaning her lens opens outward to suggest that the spiritual core at the heart of modernist purity can be found in the everyday.

Her operating principle appears very similar to the automatism of early surrealist practice. Budge has said,” I work in a spontaneous manner as an attempt to allow information from my subconscious to surface.” But what are we to make of her souped up cartoon-like palette? How do you explain the presence of ceramic hard hats with totems and the suggestion of Max Ernst? The implication is that just as early modernism was co-opted by popular culture; contemporary art practice can reclaim the impulse behind early modernism by way of popular culture.

But this isn’t simply a re-examination of previous movements, instead in Budge’s case it becomes an inclusive cycling outward where possibilities expand. The overall effect of the work has a direct connection to Freud’s theory of the uncanny. When the familiar becomes unfamiliar through repression the ultimate effect is a kind of disorientation as a result of the inability to distinguish between the real and the unreal, the animate and the inanimate.

In Susan Budge’s work a profound moment of disorientation comes when all of the cues for our collective experience of the work come slamming together in totally unexpected ways. What we are left with is our lust for the object, our need to make meaning out of it and our willingness to take a leap of faith with an artist who has given us good reason to trust her. We appear to have come full circle to a totally intuitive appreciation for an object, which inexplicably moves us.

The totem is a central theme in Budge’s work. In “Blood Moon” the conventional phallus association of the totem is subverted by creating a Cousin It-like creature whose stumpy abject form has red lens shapes at about eye level. Each eye is on opposing sides of the figure, one convex and the other concave suggesting that whether viewing out or in, some distortion will Occur. The entire figure is covered in a syrupy poured glaze, which feels like either the residue of countless rituals or the effects of years of exposure to the elements. It has the appearance of a mute oracle or a thumb shaped marker of a lost civilization.

In pieces like “Muse” and “Psyche” the totem is recouped in female form. The curves and cinched waists of both figures suggest a corseted dowager simultaneously authoritative and constrained, their décolletage marked by a graceful bustier dip. Limbs are only hinted at by petal-like flippers, which curve downward in a comic muscular pose.

In “Hawthor” pubescent nipples protrude from a zigzag Teletubby figure whose little boy blue glaze would feel completely at home in an alien’s nursery.

The only orifice in “Suspense” is located vaguely where a mouth should be, but it is more reminiscent of genitalia or an “innie” belly button. The conflation of sex, voice and birth leads the viewer to reassess identity from primal urge to maternal connection.

The female form is revisited in “Orpheus”. Its arms are raised in a balletic posture, but are equally suggestive of curled horns. A metallic glaze that seems to armor the figure in a protective sheath reinforces this conflict.

“Tribute” takes the familiar form of the hard hat and through repetition defamiliarizes it into both pure form and new associations. This most male of artifacts appears oddly female in Budge’s hands either as fertile protruding bellies or as forty distended breasts, nipples and stretch marks intact. Either way the viewer is made aware of the vulnerability of the human form by focusing on a man made exoskeleton.

Much of the Twentieth century in the arts can be seen as the separation of the mind and the body, the idioplastic and the physioplastic. The assumption has been that talent was incompatible with rigorous conceptualization. And while this was a reasonable response to the craft chauvinism of the salon tradition, some part of the marginalization of art making over the last hundred years can be attributed to this condition. Talented artists frequently found themselves relegated into craft ghettos. Serious inquiry into the meaningfulness of a language was seen as privileging the object. But if art is ever going to play a more central role in the culture, artists are going to have to reacquaint themselves with the tools that have created a broader discourse historically.

Susan Budge makes a very strong case for the idea that articulation and iconography can exist on an equally high plane. The beauty and complexity of her work make it clear that these things were never mutually exclusive. Through the seduction of her talent and the breadth of her ideas Susan Budge offers a reconnection to the origins of art making. If the earliest cave paintings and fertility figures were a form of sympathetic magic Budge has filtered that vision of the artist’s role through the warped prescription of popular culture to give the world a new Venus of the Saturday morning cartoon.

Peter Drake is a New York artist who has shown internationally for twenty years.

Meet Susan Budge

Bold Journey, October 24, 2024

We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Susan Budge. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Susan below.

Susan , so good to have you with us today. We’ve got so much planned, so let’s jump right into it. We live in such a diverse world, and in many ways the world is getting better and more understanding but it’s far from perfect. There are so many times where folks find themselves in rooms or situations where they are the only ones that look like them – that might mean being the only woman of color in the room or the only person who grew up in a certain environment etc. Can you talk to us about how you’ve managed to thrive even in situations where you were the only one in the room?

Early on, I learned that you only get one chance to make a first impression. Due to that reality, I have tried to look my best in most situations. Coming of age in the seventies-eighties, as a woman in Texas influenced my choices of hairstyle and makeup. People can not help judging one another by the way one looks. I guess the trick is figuring out what judgement you want your appearance to evoke. As I entered the art market, it surprised me when a patron in a gallery exclaimed “but you don’t look like an artist!” Up until that point, I had not thought about what an artist is expected to look like. I laughed and he bought my work. In fact, he became one of my best collectors. Around the same time period I was applying for college teaching positions. A department chair told me that I was the only person who had applied for the ceramics teaching position wearing a skirt and high heels. My credentials were what the committee was looking for, and I was hired to head the ceramics program at San Antonio College where I earned tenure, a NISOD teaching award and full professor prior to my retirement.. It wasn’t until recently that I realized I want to make a memorable impression. That I want to present myself in a way so that people will remember something about me. When I go out in public, I try to be in the right frame of mind to interact with the people I come in contact with. To make a good impression does not just reflect your appearance, it includes how you interact with and engage people. I came to realize I am an introvert, so sometimes I have to psyche myself up for social occasions. I have also come to realize that my age is affecting my appearance, which in turn effects the judgement I evoke. Now I ‘m making some of my artworks for personal adornment. Accessorizing myself with my art work makes conversation starters for continuous marketing. Focusing on drawing attention to my work is another way to share it with you. As my work has always been my life’s driving force, I must share it. That’s why it has become so important for me to have my work in museum collections, and public art installations. “How to be effective/successful even when you are the only one in the room that looks like you”… present yourself in the best-most professional manner that is comfortable for you. You have to be comfortable in your own skin and remain true to yourself.

Thanks, so before we move on maybe you can share a bit more about yourself?

My art work is the culmination of life experiences filtered through my psyche and processed in the studio. These works reference recent and childhood memories. Surviving trauma creates a desire for protection. Facing the end of fertility activated my psyche to reference Paleolithic goddess figures linked to motherhood. When facing the responsibility of being a single parent, the realistic eye emerged as a reminder of being watched. My biomorphic forms are influenced by ancient artists, like the creator of the Venus of Dolni Vestonice , and the Venus of Wilendorf which inspire at once, the duality of sensuality and maternity. Toys assists in retaining joy even when life offers continuous challenges. Respect for nature and the need for spiritual grounding infiltrate forms. My studio work is challenging, meditative, cathartic, all necessary practices to maintain sanity in a constantly evolving society and world.

My preferred creative process is spontaneous, as was likely the case of ancient artists. With the Surrealists, I celebrate the unexpected, the element of surprise, and paradox. By working intuitively, we allow subconscious thoughts to surface. According to André Breton, we “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality” or surreality. Like Kandinsky, I imagine things having a secret soul that is silent though it speaks. Art imitates life and life is fulfilled through art. With my work, aspects of life continue to be explored and shared through the medium of clay, bronze and stainless steel.

If you had to pick three qualities that are most important to develop, which three would you say matter most?

1. Tenacity

2. Education

3. Tenacity

Find what you love to do and figure out a way to keep doing it. I supported my art career with a lot of different jobs. Education does not have to be formal, although I have three degrees from different universities. You learn through experiences and travel. I was not the most talented student in my classes, but I am the one who stuck with it… tenacity.

Any advice for folks feeling overwhelmed?

When facing a monumental task, my mom told me just do a little bit at a time. Take breaks, walk away, then come back and do a little more. For me, the breaks can be, taking a walk, being in nature, reading, playing with the animals, anything that gets you away from the stress of the task at hand. Each time you go back to it and see a little progress, it gives encouragement to proceed. Then, once you really get into it, push on.

Meet Susan Budge | Artist

Shoutout HTX, January 24, 2024

We had the good fortune of connecting with Susan Budge and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Susan, what role has risk played in your life or career?

Choosing to pursue a career in art for me was less of a career choice, and more of a requirement. Working with clay became something I had to do. Taking risks is definitely part of the equation, and how to calculate the risks requires consideration… it’s a gamble… if you live at the poverty level (which I did for a few years) you can’t gamble at all. If you live slightly above the poverty level, then you can calculate the amount of money you can afford to loose.

The first big risk I took was very early on- when I decided to devote myself to a career in art. I knew that I would have to work a job to support my art career, so needed to find a job making the maximum amount of money in the minimum amount of time, to have time and energy to make art work. Flight attendant seemed perfect as they typically work 3 days on and 4 days off, so I became a flight attendant. I went to graduate school at the same time, so I worked red eye flights in to work on research papers as passengers slept. That was a burn out job and synchronicity had the airline going out of business right when I was a the end of my rope. Anxious about being unemployed I applied with more airlines. When I was about to move for a new job I realized I could not be a flight attendant anymore and needed to concentrate on my art. A couple of waitress jobs paid the bills while I finished getting my MA at UHCL, and then I applied for my first residency with the Texas Commission on the Arts. The two residencies that followed revealed my love of teaching art.

The biggest risk I have taken in recent years was to invest in having my work cast in bronze and stainless steel. It costs a lot and after I did the first one, I got so excited about it that I had to do another, and then a third. Three big bronzes is a significant investment which caused some anxiety, realizing that I could have bought a new vehicle, but, ultimately, Heidi Vaughan sold all three.

The hardest decision, which was a big risk, was when to retire from my tenured teaching position at San Antonio College. I had reached the rank of full professor and had a wonderful ceramics facility, but was aching to return to Houston and devote all of my time to raising my son William(who was then 11 years old) and my studio practice. After careful consideration and planning with my accountant I took the leap. Confirmation that I had made the right decision was immediate as I was awarded a residency at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft and was invited to teach classes at Art League Houston and the Glassell School of Art. William thrived in our new environment. Stress related illnesses ceased. My art career advanced in unexpected directions and before I knew it my exhibition schedule was overwhelming. In 2017 my work was included in 22 exhibits including a museum show that I was invited to curate and a solo show at Redbud gallery. In 2018 I realized I had to adjust my work/life balance and that has been a continuing challenge. When I first worked in clay, I knew it was my favorite medium, and a few years after that, I realized I would work in clay all my life… it is absolutely what I feel I am meant to do. Still, we all need some sense of balance and artists need time to play, observe and reflect in order to keep their work fresh, sincere and authentic. 2018 I was invited to a residency in Germany. It was expensive and the return on the investment was intangible yet very valuable. 2018 I had my first show with Heidi Vaughan Fine Art and have had continuous success working with her. My recent show, “Dreams, Visions and Desires” contained 60 sculptures created in the previous 9 months. It is a realization of hard work paying off and dreams coming true. 2019 I met and married singer/songwriter Rick Paulson who has devoted countless hours and energy to assist me in all areas. Love, devotion and hard work created a new studio, the “Stardust” installation at the Silo’s, multiple installations at Art Museum TX in Katy and Sugarland, The Biblical Arts Museum in Dallas, Heidi Vaughan Fine Art, “A Gift from the Bower” at the Loche Surls Center for Art and Nature (LSCAN), and Public Art installations in San Antonio and Houston. In the past two years we have worked through my breast cancer diagnosis and the multiple surgeries that have followed. With the help of my loving partner, and a wonderful medical team, I have survived, been declared cancer free, and regained my strength and stamina. One of my favorite quotes is from James Surls (one of my all time favorite sculptors and friend)… he said “Do what you want to do. Don’t do what you don’t want to do”. Another is from Constantin Brancusi “I give you pure joy”, and another is Kandinsky, “everything has a secret soul which is silent more often than it speaks”. Another, “don’t try to push the river” (source unknown). Duane Michals said, “Time is not what you might think, it is and isn’t in a wink” and “The best part of us is not what we see, it’s what we feel.”

I hope that through my work I can evoke feelings in you, feelings that evoke some of the mystery, passion, meaning, joy, connection, amusement and love that life has to offer.

Can you open up a bit about your work and career? We’re big fans and we’d love for our community to learn more about your work.

Touching clay for the first time was my epiphany. My work is the culmination of over forty years of exploration. The tactile quality is sensuous, immediate and gratifying. The duality of clay has engaged me as I explored the paradoxes of life: Soft/hard, fluid/static, plastic/rigid, vulnerable/strong. Fired ceramics can be pulverized to dust, or last thousands of years.The worlds oldest ceramic object, to date, the Venus of Dolni Vestonice, is reportedly 26,000 years old. Likely to have been a fertility figure, akin to the Venus of Willendorf, it inspires at once, the duality of sensuality and maternity. My preferred method of creating is spontaneous, as likely was the case of my ancient fellow artists. By working intuitively, we allow subconscious thoughts to surface. According to André Breton, we “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality”, or surreality. With the Surrealists, I celebrate the unexpected, the element of surprise, and paradox. My abstract forms have been characterized as celebrating the female reproductive system while the ceramic hard hats have been associated with protruding pregnant bellies or voluptuous breasts. Like Kandinsky, I imagine things having a secret soul that is silent though it speaks. Art imitates life and life is fulfilled through art…with my work, aspects of life continue to be revealed through “Dreams, Visions, & Desires”.

Every semester I told my students: “I was never the most talented in class, but I loved making things, so I persevered and that has made all the difference”. The road may be long, and sometimes very hard, but if you can maintain your integrity and vision, live with gratitude and compassion, be kind, never give up, believe in yourself and your dreams, you will succeed.

I am proud to have survived abuse, and to have raised my son as a single mom: to have been a tenured professor who, educated, motivated, and started an endowed scholarship fund, to have persevered through illness and despair: to have a strong work ethic and moral compass: to be a considerate, loving, wife: and to have learned the value of forgiveness, even self forgiveness, as we are all flesh and blood and bones, imperfect and turning to dust.

It thrills me when people want to own my work, and I love it when my work is on display through exhibitions in galleries, museums, and public installations. Currently my works are in the collections of 10 museums, numerous outdoor installations and public buildings.

I’m excited about building a big new kiln, making more work in clay, getting more works cast in bronze/stainless steel, getting more gallery representation, museum shows, spending more time with family and friends on the ranch, going snow skiing and having more fun!

If you had a friend visiting you, what are some of the local spots you’d want to take them around to?

Houston’s art scene is rich and diverse- many choices- the Menil, HCCC, Redbud, Heidi Vaughan and Locke Surls Center for Art and Nature shouldn’t be missed For live music/dancing, wherever my husband’s band “Sevens Edge” is playing, and for dining outside of Houston, Repka’s has the best crawfish in Texas and Anthonie’s Market Grill in Simonton has great food and atmosphere, as does The Wine Bar at the Grande Fayette Hotel in Fayetteville.

The Shoutout series is all about recognizing that our success and where we are in life is at least somewhat thanks to the efforts, support, mentorship, love and encouragement of others. So is there someone that you want to dedicate your shoutout to?

There are so many dear friends, patrons and family who have helped me to acheive success, starting with my grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles, brother, but none as much as my husband Rick Paulson and my son William Budge. Directors of galleries and arts Organizations, Rick Hernandez and the Texas Commission on the Arts, Sara Morgan, Clint Willour, Sarah Darro, Mary Headrick, the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Hans Molzberger, Hilmsen, residency programs. Joan & Jerry Herring,(Fayetteville), Gus & Sharon Kopriva, Heidi Vaughan, Judy Youens, Tom Andriola, David Hardaker, Linda Darke, Gus Kopriva, Volker Eisele, Jeff Forster, Patrick Palmer, Glassell School, Emily -Sloan Mystic Lyon, Art League Houston, Women’s Caucus for the Arts, Lawndale, (Houston) Charlene Rathburn, Lisa Ortiz, Ana Montoya, Bill FitzGibbons, Felix Padron, Umberto Saldana, James Gray-Rialto, Jon Hinosa, Say-Si, Karen Calvert, Phil Hardberger, David Rubin, Bill Chiego, San Antonio, Ana Villaronga-Roman, Katy, Sugarland, Phillip Eirich, Kansas City, Ed Roberts (Loveed Fine Art, New York). Artists, James Surls, Charmaine Locke, Jesus Moroles, Jeff Whyman. Richard Fluhr, Joe Havel, Robert Morris, Thedra Cullar-Ledford, Alton Dulaney, Michelle O’Michael, Susan Plum, George Tobolowsky, Joe Barrington. Countless patrons, Alton & Emily Steiner, Buddy Steves & Roweena Young, Steve Alpert, Lonnie & Terri Gates, Katherine & Andy Persson, Rob & Tara Tomicic, Melinda O’Connell, Jan Rayburn, Billie & Marvin Chasen, Jill, Fred, Leslie, Andy Huston, John Davis Rutkauskas, Nick & Candice Goodwin, Barbara Faber & Ray Hylenski, Ann & Dennis Webb, Don & Crystal Owens, Amy & Rick Cherry, Jill Joe Diaz, Josie and Jonathan Kaplow… Writers/Publishers, Catherine Anspon, Donna Tennant, John Bernhard, Molly Glentzer, The Houston Press, Glasstire, Dan R. Goddard, Diana Roberts, TX, Southwest Art CO, Peter Drake, NY. My teachers, mentors, Sara Waters, Verne Funk, James Watkins, professors at TTU. Peter Voulkos, Rudy Autio, Jim Leedy, Paul Soldner, Jun Kaneko, ceramic artists. Nick DeVries, Steve Reynolds, Ken Little, Francis Colpitt, professors in graduate school who encouraged my growth, as well as so many others who have supported me through the years.

5 Houston Art Shows You Need to See — ‘Tis the Season For Creative Joy

These Artists' Powerful Works Are Worth Catching

Haley Berkman Karren, PaperCity, December 12, 2023

The holiday season is a time of joy and celebration, and of course — art. Yes, art. Art can make any season more interesting. Luckily, Houston is still awash in interesting art during the holidays.

“Dreams, Visions & Desires” at Heidi Vaughan Fine Art

Following a lengthy health battle, sculptor Susan Budge triumphantly returns with an exhibition of nearly 60 works created in just nine months. The celebrated ceramicist works intuitively, with no planning in advance. Budge frequently references themes of motherhood, spirituality and partnership in her otherworldly, surreal forms that vary dramatically in size and scale. From diminutive pieces to staggering totems.

Budge also has several jewelry pieces with her signature eye symbol available for purchase.

Susan Budge’s “Dreams, Visions & Desires” is on view at Heidi Vaughan Fine Art (3510 Lake Street) through Sunday, December 31. Learn more here.

Arthouston Magazine

Fall/Winter 2022/2023

“With my work, I attempt to evoke the mystery of all we seek to understand. To recognize everything has a secret soul and connection. As in life, the challenge is to balance strength and fragility.”

Susan Budge is an American sculptor working in clay and bronze with influences from Biomorphism and Surrealism. Budge holds a BFA from Texas Tech University, MA from Uni-versity of Houston Clear Lake, MFA from University of Texas at San Antonio.

Budge’s work has been in hundreds of exhibitions around the world, and is in the permanent collections of the Smith-sonian, the Honolulu Museum of Art, the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art, the Fuller Craft Museum, the San An-tonio Museum of Art, the San Angelo Museum of Art, the Art Museum at Northern Arizona State University, the Art Museum of South Texas, the New Orleans Museum of Art. Budge has received numerous public com-missions, residencies and awards, including, Artist of the Year for the Texas Accountants and Lawyers for the Arts in 2004.

Her teaching career began with Artist in Education Grants from the Texas Commission on the Arts in 1988. She was the Department Head of Ceramics at San Antonio College as a tenured professor. Prior to her 2015 retirement, she earned a NISOD excellence in teaching award and established an endowed ceramics scholarship fund.

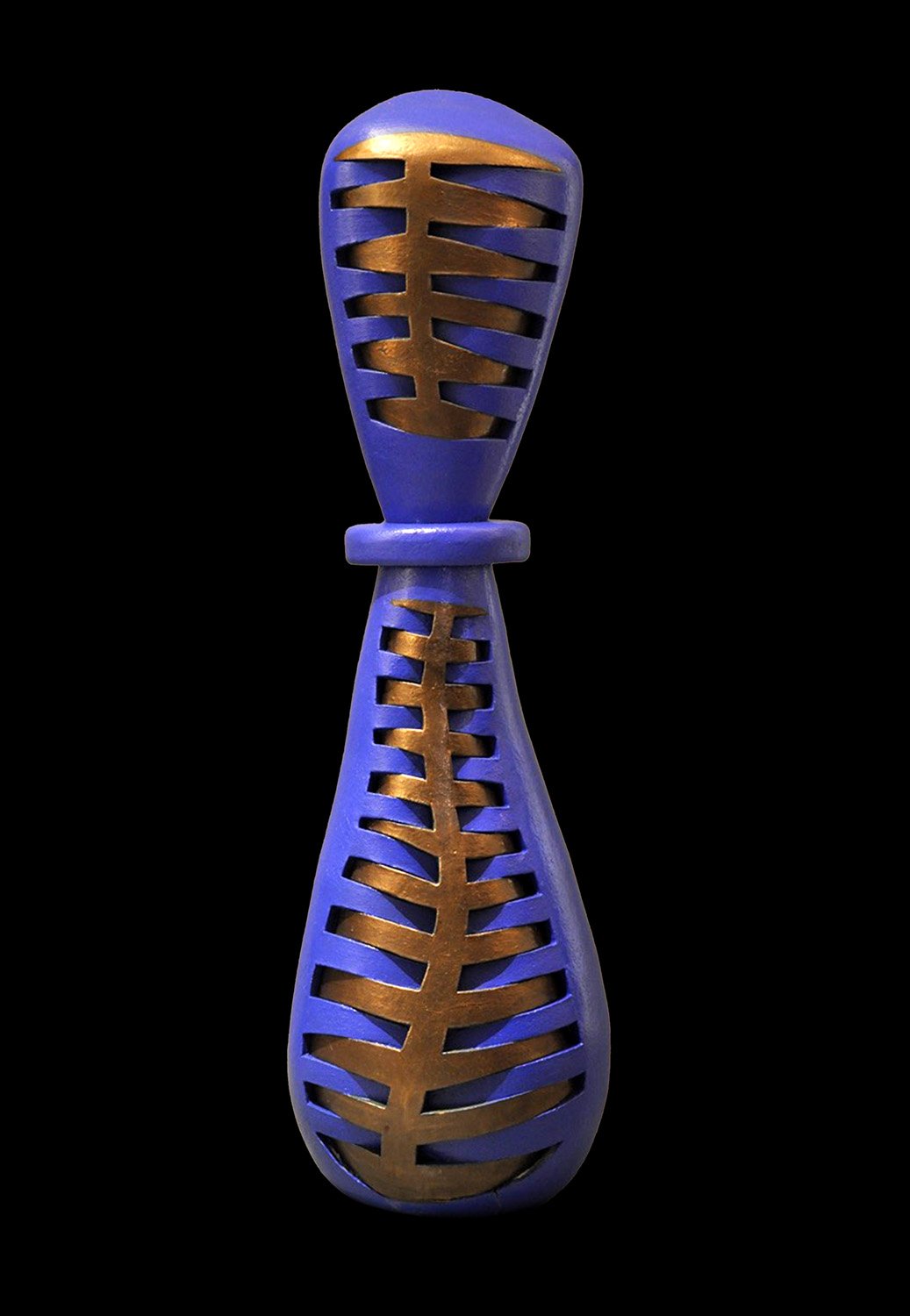

“Touching clay for the first time was my epiphany. The physical, sensual, direct qualities of this material have challenged me for over forty years. I prefer to work spontaneously in the studio in order to allow subconscious thoughts to surface. As a result, the works reveal issues at various stages of life, reflecting the concerns of the time. Works containing an eye began as a nod to the ‘All Seeing’ and reappeared following the birth of my only son. His constant gaze reminded me to “be good”, to set a good example. The eyes also reflect the notion of Kandinsky that: ‘Everything has a secret soul, which is silent more often than it speaks.’ The cut forms incorporate a technique that is challenging and meditative. In my work I enjoy the use of paradox: balancing fragility and strength through technique and material.”

Budge maintains an active studio practice at her rural studio near Houston. www.susanbudge.com

Susan Budge has worked with clay for as long as she can remember, saying that “touching clay for the first time was an epiphany.” Her work has many references to the Paleolithic “goddess” figures from prehistory that were linked to motherhood and fertility. Although Budge has practiced as a ceramic artist for more than 40 years, the birth of her son in 2003 has had a direct influence on her work since. The fierce instinct of maternal protection manifests itself in the large totemic pieces, which she refers to as guardians or sentinels. Budge has said that these guardians also represent the spirits of people she has loved who have passed away.

Budge is fascinated by the human figure. Some like “Gold Guardian” are tall and slender, while others like “Eye Spy Red” embody the curvaceous female figure and are intensely sensual. Many have a realisticly painted eye embedded in them, usually near the top in what is perceived as the “head” of the piece. In the smaller works, which she refers to as “objects of affection,” the eye is located in the center. According to Budge, she began using the eyes when she noticed that her young son was watching her constantly while she was working in the studio.

Budge has an affinity with the surrealist reliance on the subconscious in the creative act. By working spontaneously rather than rationally, her sculptures are pushed to reflect that tendency. A bulbous piece titled "B.B.'s Ghost" mimics the form of a lover who has passed away, but she did not realize that until it was completed. “When I wrapped my arms around the sculpture to pick it up, I realized that its circumference was the same as his,” she said. Its subtle coloration is the result of a five-day wood firing, during which time the fumes from the burning wood created intriguing markings and glass deposits on the piece.

Budge’s surfaces range from gleaming reds and blues to more subdued grays and golds. Displayed on brilliant red walls and pedestals, these anthropomorphic sculptures create a powerful and compelling environment.

HOUSTON OUTDOOR SCULPTURE SHOWS REVEAL MORE THAN ART

'Art on Long Point' and 'True North 2020' bring sculpture shows to streets perfect for exploring

Molly Glentzer, Houston Chronicle, April 28, 2020

Carter Ernst’s “Pointing,” a big sculpture of an attentive Labrador retriever, appears to have strayed.

“Pointing” debuted in 2014, when it was up for nine months as one of the first works of “True North,” the revolving show of public art that’s designed to be a people magnet along Heights Blvd.’s leafy, 60-foot wide scenic right-of-way. Built in the early 20th century for the city’s first electric streetcar system, that esplanade is lined by a genteel landscape of restored Craftsman bungalows and trendy restaurants. “Pointing” looked like the family pet there.

Now the sculpture has re-emerged at 8141 Long Point, in Spring Branch. The art hasn’t changed, but everything around it has. The pooch looks more pitiful but maybe also more purposeful, with its paws balanced on concrete blocks in the wide-open, asphalt parking lot of a shopping center in transition.

“Pointing” is one of seven sculptures in “Art on Long Point,” a new program modeled on the Heights show that also will rotate works every nine months. Josh Hawes, deputy executive director of the Spring Branch Management District, said the sculpture program is an element of a 15-year plan to transform Long Point into a grand thoroughfare.

The pandemic has not helped, but commercial and residential redevelopment are continuing, Hawes said. The new owner of the shopping center where Ernst’s sculpture is displayed has brought in a yoga studio and a coffee shop. “We’re trying to walk a fine line on economic development,” said Hawes. “We’re doing a huge push for local restaurants.”

He said the district spent $50,000 to get “Art on Long Point” up and running because the community wanted it. With more private property than public space along the street, businesses are sponsoring most of the sculptures, and Hawes said the response has been enthusiastic, and some businesses want to keep their pieces.

Still, he admits, everything around the art program has a ways to go.

Driving about six miles on Long Point from Gessner to Hempstead Rd., I had to U-turn and double back more than once to spot the sculptures. Finding the art was a scavenger hunt amid the visual clutter of a hard-working street of used car lots, tire shops and barber shops, furniture stores and laundromats, clinics and dollar stores; and a wealth of Korean barbecue joints (this area is home to what is said to be Houston’s largest Koreatown), carnicerias and panaderias. Houston’s only torteria is there, and a Mexican-vegan place that I will go back to, some day.

An intrepid urban trekker could spend the better part of a day walking that show. I wouldn’t. But it’s a revealing drive, especially combined with “True North 2020.” Both shows allow for comfortable social-distancing.

I prefer the west-to-east route, starting at Gessner and Long Point.

The first three pieces are delightfully scrappy, all made with found materials. They are within a third of a mile of each other, so you can park and walk between them. Randall Mosman’s “Stilt House,” a towering steel structure, has plants and shards protruding through its roof. Anthony J. Suber’s “Time Traveler,” an imposing mound of lumber and steel, has a primitive human head. Robbie Barber’s “Southern Comfort,” a mobile-home-turned-baby-carriage, sits in a sunny corner of Haden Park.

Back in the car, look for Keith Crane and Chris Silkwood’s mosaic tile “Dazy May,” which could depict a butterfly or a flower. It sprouts from the lawn beside St. Peter United Church of Christ. While you’re there, take in some history. Spring Branch was settled by German farmers and merchants starting in 1830, a few years before the Allen brothers landed in downtown Houston. The old wood structure at the west end of the modern, brick church dates to 1848.

Walk a block or so and you’ll come to Susan Budge’s ceramic, totemic “Harvey,” a graceful, abstract form that’s installed in a small grove of crepe myrtles with benches — a somewhat serene space, if you can ignore the traffic. Drive on, and you’ll find Patrick Medrano’s “Our Lady of the Island,” a surreal and assertive figure with her hands on her hips and a building for a head. Ernst’s “Pointing,” made of a patchwork of resin-coated fabric on a steel frame, is almost across the street.

To get to the Heights, turn right onto Hempstead Rd., then left onto 11th. This plunks you just about in the middle of “True North 2020,” which has eight sculptures.

This is a pleasant walk of about a mile in each direction, or a four-mile loop. Whether it’s a matter of the curating or the setting, I don’t know, but “True North 2020” feels more refined to me than “Art on Long Point.” Co-curators Linda Eyles, Simon Eyles, Chris Silkwood and Kelly Simmons chose works with an environmental theme.

Head south first, and you’ll encounter a large head of cabbage. That would be Bill Davenport’s polymer concrete “Big Cabbage,” which measures 7 feet in diameter. Okay, not so refined, but very, well, green. “Hard Rain,” Jack Gron’s 10-foot aluminum and painted steel sculpture, looks like a tilted water tower from a distance. The top turns out to consist of puffy cloud forms. Long rods form the “rain” pelting colorful geometric forms at the base which represent a cityscape.

Vincent Fink’s “Dodecahedron” looks like a clear, giant gemstone, painted with images of sacred geometric forms. This piece could be at home outside the Houston Museum of Natural Science. So could Jack Massing’s inventive “Loculus,” a functional wind vane in the shape of an oil derrick powered by a wrench and a huge pencil. If you’re lost, you can find your place on Earth, literally, by viewing the geographic coordinates on the structure.

North of 11th, Leticia Bajuyo’s playfully serious “Forces of Nature: Blue Skies, Slinkys, and Hurricanes,” hugs the ground, as if someone dropped a couple of monumental donuts there made of steel, blue tubing and artificial grass. Maybe I was just hungry. Joseph Havel’s evocative, nine-foot bronze “On History” rises near the local library. A ghostly sliver of thin forms rising from a small stack of books, it provokes questions about the evolution of the Heights. Next comes Sherry Owens and Art Shirer’s sophisticated “Carbon Sink,” sculpted with discarded crape myrtle cuttings that have been carbon finished, to evoke a depository for greenhouse gases.

The tour ends with a whiff of whimsy, minus the implied barnyard odors, conceived by the late Bob “Daddy-O” Wade before he died last Christmas Eve. Kids love “El Gallo Monument.” Its brightly-colored pigs, piglets and rooster were inspired by the “roadside stuff” Wade remembered along old Texas highways.

Redbud Gallery owner Gus Kopriva, who had a hand in both shows, has known both neighborhoods his whole life. He grew up in the Heights, and worked as a stock boy when he was in high school for an uncle who owned UtoteM convenience stores in Spring Branch.

As a German/French American, he especially loves the history of Spring Branch. The COVID-19 pandemic had him thinking about an old cemetery not far off Long Point. “It’s full of yellow fever victims,” he said. “During that epidemic, people moved to Spring Branch to get away from the bayou and its mosquitoes. Of course, it followed them.”

GLASSTIRE: LAWNDALE’S BIG SHOW: TOP TEN OF 2016

Year after year, Lawndale Art Center’s Big Show in Houston feels like a display of mass chaos—a kind of flea-market hunt for the odd diamond (in the rough), and admittedly, that’s part of the fun. But this year was a little different. Even with 105 works by eighty-seven artists covering two floors, it feels like a cohesive show. It’s the best Big Show I’ve seen. What happened?

A few things. This year Lawndale got rid of its submission fee, notably increasing the number of submissions (to 1,389, up from 972 from the previous year). This no-fee novelty compelled more than 150 extra Houston-area artists to submit more work. But this of course meant the show’s jurors had to sift through more to whittle the show down to a little over a hundred works on view.

A quick glance at the jurors’ statement will reveal how much thought they—Apsara DiQuinzio and Tina Kukielski— put into organizing this show, as most of their statement gives us a play-by-play through each of Lawndale’s three galleries. DiQuinzio and Kukielski didn’t fall into the trap that some Big Show jurors do—and almost all of them are from out of town—which is to gravitate toward a caricature of what they think Texas art is supposed to look like. Instead they brought a strong curatorial stance, as just about every piece communicates notions of familiarity and displacement. That may sound broad, but it’s thoughtful and appropriate for Houston, a city known for its friendliness, diversity, sprawl, and schizophrenic lack of zoning. Click here to continue reading on Glasstire.

THE BIG SHOW 2016

Susie Tommaney, Houston Press

Not all artists are starving, but a little help never hurts when it comes time to choose between ramen noodles and paint. So when Lawndale Art Center put the kibosh on the submission fee for consideration in the annual exhibit The Big Show, artists within a 100-mile radius took notice. Stephanie Schumann Mitchell, Lawndale’s executive director, says it’s all about leveling the playing field for young, mid-career and established artists. She says Lawndale received the largest number of submissions in recent memory (1,389 pieces by 517 artists), so it’s good that the center has lined up not one but two established curators to jury this year’s show: Apsara DiQuinzio (Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and Phyllis C. Wattis Matrix Curator at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive) and Tina Kukielski, executive director of New York’s ART21. “Tina and Apsara have curated shows before. They work very, very well on shows together,” says Schumann Mitchell. “They’re both whip smart.” For those who haven’t attended before, The Big Show (which has spurred a whole other exhibit in town for those who don’t get in) offers a great way to view wall-to-wall art, follow the career progression of artists, and begin to form your own collecting taste. It also gives artists the opportunity to take a chance and experiment, without cowing to gallerists’ demands for salable art, though the results are often sublime.

There’s an opening reception from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. on July 22. Regular viewing hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mondays to Fridays, noon to 5 p.m. Saturdays. Through August 27. For information, call 713-528-5858 or visit lawndaleartcenter.org. Free.

From small show to “The Big Show,” exhibits offer more than eye candy

Molly Glentzer, Houston Chronicle, August 12, 2016

'The Big Show'

Any artist practicing within 100 miles of Houston can enter Lawndale Art Center's popular annual open-call show. Opening a door to self-taught newbies as well as academically trained professionals, "The Big Show" is always fun to see.

It looks great this year because jurors Apsara DiQuinzio, from the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, and Tina Kukielski, who directs New York's digital-media-focused Art21, noticed themes and perhaps chose the show accordingly.

Sifting through a marathon of nearly 1,400 submissions, they selected 105 works by a record 87 artists. They awarded the $3,000 top prize to a work you could easily miss amid the many large canvases: the dark and layered ink drawing "First Cause" by Katya Vassilyeva. It's one of the smallest pieces on a wall whose works all have graphic, black-and-white drama.

Elsewhere across the huge O'Quinn Gallery, it looks like a lot of Houston artists have been taking classes in Cubism and Surrealism. Some very retro stuff there.

The display in the Grace R. Cavnar Gallery spotlights figurative work that ranges from meticulous to loosely expressive and barely there. David P. Gray's "The Calder" engaged me with its luminous realism. It depicts two men sitting in a retro diner, deep in conversation, with a small Alexander Calder print inexplicably propped on their booth.

I also lingered at Rajab Sayed's "Daydreamer," which feels Andrew Wyeth-like: Its husky, plaid-shirted figure gazes at a gray landscape through the window of a white room.

Upstairs in the Horton Gallery, I was mesmerized by the dangling bodies of Daniela Antelo and Clay Zapalac's one-minute loop video "Hanging" - and quickly saw parallel tracks in the lines of the room's other works, especially the crocheted yarn strips of James Kerley's "Agility Text (Difficulty Level 5)," on the floor; William Dixon's "Wait Right There," a large photograph of a line of blue plastic chairs; and Cassie Skelly's "Stand Tall," a close-up photograph of human feet whose ring-clad toes splay out as they try to elevate a body.

But then I got enthralled with Christy Karll's "More than Enough," a three-minute video whose digitally altered imagery led me down a road in a bright, dreamy haze.

More than enough, indeed.